Portrait of Stella Yellow Shirt and baby, Dakota Sioux woman seated, three-quarter length, facing left, with baby on back. Photograph by Heyn Photo, Omaha, Nebraska, No. 291, 1899. From the Library of Congress More Native American portraits | More Hein and Hein & Matzen photographs [PD] This picture is in the public domain (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

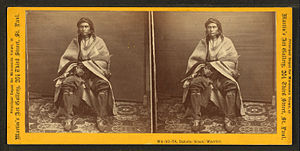

Portrait of Stella Yellow Shirt and baby, Dakota Sioux woman seated, three-quarter length, facing left, with baby on back. Photograph by Heyn Photo, Omaha, Nebraska, No. 291, 1899. From the Library of Congress More Native American portraits | More Hein and Hein & Matzen photographs [PD] This picture is in the public domain (Photo credit: Wikipedia) Wa-Su-Ta, Dakota (Sioux) warrior, by Martin's Art Gallery (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Wa-Su-Ta, Dakota (Sioux) warrior, by Martin's Art Gallery (Photo credit: Wikipedia) English: Main locations of the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom Français : Principaux théâtres d'opérations de la Guerre de 1812 entre les États-Unis et le Royaume-Uni. Español: Principales teatros de operaciones de la Guerra de 1812 entre los Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

English: Main locations of the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom Français : Principaux théâtres d'opérations de la Guerre de 1812 entre les États-Unis et le Royaume-Uni. Español: Principales teatros de operaciones de la Guerra de 1812 entre los Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) Painting by William Henry Powell depicting Perry's transfer to the Niagara during the Battle of Lake Erie. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)‘Red-Haired Man’ remembered for pivotal role in War of 1812

Painting by William Henry Powell depicting Perry's transfer to the Niagara during the Battle of Lake Erie. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)‘Red-Haired Man’ remembered for pivotal role in War of 1812in a distant native community south of Saskatoon — the home of Saskatchewan’s Whitecap Dakota First Nation — a few hundred kinfolk of the Sioux warriors who joined Dickson, Brock, Wabasha and fellow aboriginal ally Tecumseh in confronting U.S. forces 200 years ago are proudly remembering their special connection to the War of 1812 battles that helped create Canada.

To this day, the war is known among the Dakota Sioux as Pahinshashawacikiya: “When The Red Head Begged For Our Help.”

July 17, a contingent of aboriginal warriors led by Dickson had joined with a motley crew of British soldiers, English-Canadian volunteers and French-Canadian voyageurs in securing the first victory of the war: the capture of the American fort on Mackinac Island at the western end of Lake Huron — a strategically important prize guarding the entrance to Lake Michigan.

Word soon spread among First Nations throughout the colonial hinterlands that allying with the “generous” British rather than the “false” Americans — in the words of another of Dickson’s Sioux comrades, Little Crow — would best serve aboriginal interests, including the preservation of their traditional territories and the protection of lucrative fur-trade relationships.

Momentum in the War of 1812 would shift several times before a peace treaty was signed in Belgium in December 1814 that essentially declared a stalemate and restored all pre-war boundaries. The momentum shifted, in fact, several times even after the Treaty of Ghent was struck and before news of the war’s end finally reached North America in February 1815.

But by all accounts, the British-Canadian alliance with Tecumseh, Wabasha and other aboriginal leaders proved essential in preventing the American takeover of the colonies that would be joined in Confederation a half-century later — as well as the western territories that would gradually become part of the new, independent nation north of the United States.

“Our ancestors did contribute to building this nation, and it should be recognized and acknowledged,” said Chief Bear. “But it’s also a story about betrayal, too. The British and the United States signed a peace treaty on the other side of the ocean – in Europe, in Belgium — and the First Nations, of course, weren’t there to represent themselves. And all of the promises made at the beginning, like the creation of a homeland state for First Nations, that was gone.

“The United States pushed the negotiations to eliminate those promises,” he continued. “And the British abandoned their allies.”

Chief Wabasha and his immediate descendants were pushed far to the west, into present-day Minnesota, as the U.S. government carried out its aggressive, expansionist policies of the 19th century.

Eventually, in the 1860s, a branch of the Dakota Sioux sought refuge in Canada — displaying medals and flags as reminders of their people’s sacrifice in the War of 1812. The links forged between Wabasha and his British allies during the conflict was recognized in a provision of land about 25 kilometres south of Saskatoon, today’s Whitecap Dakota First Nation.

Which Diet Works?

One of the challenges of arguing that hyperprocessed carbohydrates are largely responsible for the obesity pandemic (“epidemic” is no longer a strong enough word, say many experts) is the notion that “a calorie is a calorie.”Accept that, and you buy into the contention that consuming 100 calories’ worth of sugar water (like Coke or Gatorade), white bread or French fries is the same as eating 100 calories of broccoli or beans. And Big Food — which has little interest in selling broccoli or beans — would have you believe that if you expend enough energy to work off those 100 calories, it simply doesn’t matter.

There’s an increasing body of evidence, however, that calories from highly processed carbohydrates like white flour (and of course sugar) provide calories that the body treats differently, spiking both blood sugar and insulin and causing us to retain fat instead of burning it off.

In other words, all calories are not alike.

In Rwanda, Health Care Coverage That Eludes the U.S.

By TINA ROSENBERG

After the 1994 massacre, Rwanda built a health care system that includes everyone. The United States should take note.

The Fires This Time

In the West, the populated fire zone is called the urban wildland interface, a clunky term to describe a vulnerable habitat for almost 40 percent of new homes built over the last two decades. And the fire danger will only grow, as 40 million acres of ghost forests — standing trees killed by an epidemic of bark beetles that metastasize in warmer winters — are ready to burn.

( How's that for making the harassment of those clearing firebreaks by co2 sequestration promotion worse ? .... now burning slash is 'environmentally irresponsible'. I should check out a note where I seem to recall the beetles also jumped species. )

Bark Beetle - USDA Forest Service

Bark beetle infestations create patches of forest that have trees of various ages, densities, species, and successional stages. This variation helps keep the ...

www.fs.fed.us/rmrs/bark-beetle/

No comments:

Post a Comment